The Caliph's House: A Year in Casablanca

ByTahir Shah

Thursday evening saw our book group meeting relocated from the Library to a house nearby because of an accident. We didn’t know much of the details except that an elderly man had died after a heart attack whilst driving and died on the spot. His car had ended up lodged into the neighbouring shop wall.

This morning I arrived at my Creative Writing Group to be told the sad news that it was one of our number, John Veitch, who was the driver of the car. I’ve only been going to the group for a few weeks now and am still getting to know people so I knew very little about John except that he had a very distinctive vocal style, with well rounded pronunciation and a voice that carried authority and distance. In his writings, and to other members of the group, he often spoke about his late wife whom he clearly missed.

As a group we wrote for John today and here is my tribute.

by

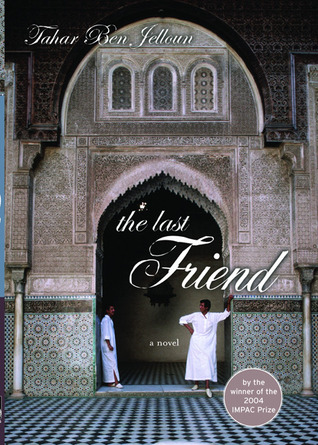

This novel is the story of a friendship between two men – Ali and Mamed. In the first part of the book, Ali recalls their friendship from its beginnings during their childhood, through their studies abroad – Ali in Canada, Mamad in France – , their involvement with the nationalist struggle, their imprisonment and military service, their marriages – Ali to Soraya and Mamed to Ghita - and their children. Being told first, the reader is easily lured into all that is Ali’s perspective and like Ali cannot understand the sudden twist in Mamed’s behaviour and the breakdown of the friendship which had survived so much and thrived over the years. From the proceeding Prolog we know Ali has received a letter from Mamed which he says is “ a letter intended to destroy me.”

The second section is told from Mamed’s viewpoint. He recalls different things about their friendship and their experiences, including more details from their imprisonment. He fills in more about his life in Sweden, their relationships with their wives and his illness. He tells about the decision to break off his relationship with Ali, to not see him and how he uses the bills for the refurbishment by Ali and Soraya of his house in Morocco as the breaking point.

The third section is from the point of view of Ramon, a friend of both, but not as close a friend to either as they are to each other. He provides a independent, non-judgemental friendship especially during the period of its dissolution. He provides the background to Mamed and his family’s return to Morocco because Mamed wishes to die on home soil. He also provides an independent view of the sorrow that Ali feels at his friend’s death.

The final section is the letter that Mamed has written during his final months in Morocco explaining why he broke with Ali. I read it as Mamed’s attempt to explain, to set the record straight, about his destruction of their friendship as an attempt to save Ali the pain of seeing him die. I found it a powerful tale of friendship, of what one friend will do to ease the pain of the other although this act itself hurts him deeply. But clearly Ali did not see it in this way. Just as the two had different memories, so they had different perspectives on the letter. Mamed seeing it as an explanation, Ali as a final blow. Just as memories are idiosyncratic and flawed so can our understanding be of the actions of others. As a reader we’ve not witnessed the events directly only through the participants one renditions. Ben Jalloun’s clever construction of the book means we need to make up our own minds about what actually happened.

ashramblings verdict 4* : a cleverly constructed, beautifully told story of friendship

_flower_FS17.jpg)

At last week’s creative writing class our tutor brought in a small, attractively glazed pot of flowering snowdrops and set us the task of using this item as a stimulus for our writing. Here’s my attempt

Phew! I’m exhausted. But I must keep going. Push, Rest. Push, Rest, Push. Push, rest. All this water, where had it come from? Squish. Squash. Push. Push. Rest. Take stock for a moment. Check the reserves. Clearly my food reserves have been impacted by wet rot. Yeah, OK, good. Just about enough. Well it normally would have been enough but this year, who knew? It was so wet. All that water to push away. All that mud to displace. Off again – push, extend, push, extend….ahggrr! Watch out! Must manoeuvre round that stone. Yes, that’s it now, easy does it, don’t tear anything valuable. Let’s try and conserve as much as possible. On I go extending, growing, pushing forward, upward through the wet dark soil. Surely I ought to be in the light soon? Ok,, concentrate, dig deeper, draw up more reserves, continue pushing onward. It’s still dark. It’s still damp. There’s no sign of light yet at all. Was it an illusion of is it getting less waterlogged? No, it’s my imagination running riot. Back to growing up, back to pushing forward, back to avoiding obstacles, back to taking hopefully not too long detours round them. Back to being careful to avoid damage to the goods in transit - pale, delicate little things and the whole point of the exercise after all. So keep a tight rein there and steer a strong course forward, upwards, lightward. Come on now, you can do it. You haven’t got all year I tell myself. One last almighty push. Push. Push. Push, no rest, Push, Push. Ah!

The Shahnameh: The Persian Book of Kings

The Shahnameh: The Persian Book of Kings Illustrated by Shirin Adl

The Shahnameh is a long epic poem written by the Persian poet Ferdowsi between c. 977 and 1010 CE . It is the national epic of Iran (Persia). It consists of some 50,000 verses telling the mythical and some of the historical past of the Persian empire from the creation of the world until the Islamic conquest of Persia in the 7th century. It is similar in status to the Arthurian legends in the UK, every child grows up knowing the stories.

This book is a retelling of some of the stories of the Shahnameh aimed at children. It was the only version that my Library system had but I have to admit it would make grand reading to or with children.

It begins with the story of Kayamars, the First King where the devil Ahriman is also introduced. As Kayamars, his sons and grandsons improve the lot of man, Ahriman bides his time and “lurks secretly in a far-off lair” before the “worm of pride” brings down the reign of Kayamars, great-grandson Jamshid and God removes his kingship. Meanwhile Ahriman has taken hold of Arabia by conspiring to murder its King and place his son Zahhak on the throne, Ahriman turns Zahahk into a evil war mongeror, placing two black snakes protruding around his head which need to be fed by the deaths of two people every day. Zahhak dreams of being conquored by a hero called Feridun. Feridoun’s mothers hides her child in the mountains, with cows and with holy men until he is old enough to successfully take on Zahhak.

The next story is a classic “love across the divide” tale, the story of Zal and Rudabeh, in which the son of one of Feridun’s champions falls for and eventually marries the daughter of King Mehrab of Kabul a follower of the Zahak. Zal is left for died in the mountains by his father for having been born with unusual white hair. There he is raised by a giant bird, who graciously returns Zal to his father when he has a change of heart regarding the boy. This story has Rudabeh lower her hair down for Zal to climb up, very similar to the Rapunzel fairy tale by the Brothers Grimm. It never fails to amaze me how irrespective of culture folk stories and fairy tales have the same themes – good versus evil, jealousy, love, friendship etc. – all the basic human emotions.

The the story of Rustam, Kal and Rudabeh’s son, who becomes the nation’s champion. Rustom fights the fiercest elephant when still a boy, acquires his horse Rakhsh and sets out to find Kay Kobad who will become King to fight off attacks from neighbouring Turanian prince Afrasyab. However, Kay Kobald’s son, Kay Kavus, was not like his father and when the devil disguised as a musician tempted him with the delights of Mazanderan he tried, against all advice, to invade and take that country which was ruled by the White Demon. He and his generals ended up blinded and prisoners of the White Demon. Rustam is sent forth to free them. He has to pass seven trials en route and with the help of Ulad finally kills the White Demon and frees Kay Kavus and his generals, installing Ulad as King of Mazanderan.

But Kay Kavus was not done fighting and raised his standard against the King of Hamaveran, subdued him and married his daughter. But the King rebelled at this and once again Kay Kavus and his generals were imprisoned only to be freed once again by the heroic Rustam. The devils were not done with Kay Kavus and persuaded him to go on and conquer the heavens. Kaya Kavus built a throne or wood and gold, which had 4 powerful eagles strapped to it chasing meat held on lances attached the the throne. Thus Kay Kavus flew higher and higher into the heavens until the eagles were exhausted and Kay Kavus fell down to earth. Finally repenting of his pride and folly he was forgiven by God and reigned peacefully for the rest of his days.

Rustam’s horse was stolen by Turanian horsemen and taken to Samangen. When Rustam approached the King of Samangan for his help in locating his horse, he met and married his daughter Tahmineh. Upon the return of his horse Rustam returned to Iran, keeping his marriage secret and leaving Tahmineh in Samangen to give birth to his son, Sohrab, who grew strong like his father whom he had never met. But the overlord of Sohrab’s family was Afrasyab, an enemy of Iran, who when he heard that Sohrab was raising an army to attack Iran and find his father planned that Sohrab should not discover who was his father and so would end up facing him in battle. This battle was a tremendous fight between the two men. Each had seen signs that the other was a relative but had been swayed by falsities from their advisors so they did not believe their own eyes. Rustam brought Sohrab down and as he lay dying the whole sad story comes out and Rustam is consumed by grief, having killed his own son.

I loved these stories, and can well imagine children in Iran being brought up on these tales and playing Rustam and Sohrab games and dreaming of a love such as Zal and Rudabeh found.

ashramblings verdict 4* – a great book for reading to your kids

by

A young girl and her recently widowed mother, without a male family member to tend their fields, have to leave their home village to seek the protection of her father’s half brother, a carpet maker, in 17th century Isfahan. He and his wife taken them in, but they are treated like servants. The aunt is manipulative and resentful of their presence but the uncle recognises the young girl’s talent for carpet design and teaches her because he has no sons to pass his skills and business on to .

Her skills increase and he lends her money to craft her own rug for sale, the sale of which will start to raise money for her dowry. In a moment of frustration with the quality of her work and choices of colours she cuts all the knots, shredding and wasting lots of expensive wool. Without dowry money her marriage prospects are non-existent and she ends up in a secret, although legal, temporary marriage, a sigheh, with the son of a horse trader. Effectively her family have sold her virginity for money on a renewable 3 month contract. She gradually realises just what is really required of her in this arrangement and her contract is extended for a second period securing her and her mother’s wellbeing for a bit longer.

However, she has always been a headstrong child and realising that she is being used by her husband who has no intention of making her a proper lifetime wife, declines the next extension. Retribution by her husband’s new wife and their social circle, the consequences of having kept the sigheh secret from everyone not directly involved, see strains put on the family’s rug business and without male protection and without money, the girl and her mother find themselves on the street without money having been tricked out of the payment for her rug by a Dutchman buyer. Finding shelter with a poor family and with her mother becoming sick, she risks everything in an attempt to keep them alive and to survive.

This a coming-of-age tale which sees the girl, unnamed throughout the book, transform from a headstrong child, doing the rash and impulsive thing without thinking of its consequences, into a bold and determined young woman in charge of her own future. It has all the twisted turns in fortune as seen in the knotted threads of one of the carpets so vividly described in the book – her change in circumstances in her uncle home, the vindictiveness of her aunt, the opulence of her husband’s home, the squalor of loom worker Melaka's one room shack, her insightful relationship with Homa the woman who runs the hamman, her friendship with the neighbour's girl Naheed, how she learns the tricks of how to survive begging from the blind beggar – all these experiences knot together to form the up and down pattern of her life. That life story is interspersed with folk stories, told mainly by her mother, to build up as rich a storyboard as any Persian carpet’s design.

I absolutely flew through this book, loving not only the story the author had put together but also the interspersing Iranian stories. Each of these begins with “First there wasn’t and then there was. Before God, no one was” which in an Author’s Note to the edition I read is described as a rough translation of the Iranian equivalent of “Once upon a time” expression used at the start of European folk and fairy tales. Of the seven such tales in the book, two are the author’s own and five are retellings. I was also intrigued to read that the book’s title is taken from a poem called “Ode to a Garden Carpet” by an unknown Sufi poet c 1500 which portrays the garden carpet as a place of refuge that stimulate visions of the divine, whereas within the book the blood of flowers is the dye created from flower petals. This poem is so beautiful I reproduce it here:

Ode To A Garden Carpet – By an unknown Sufi Poet (Circa 1500)

ashramblings verdict : 4* This rapid read will ensure that you’ll never look at a Persian carpet the same way again!

Beneath the Lion’s Gaze

Beneath the Lion’s Gazeby

Scottish author David Ashton first wrote an Afternoon Play for BBC radio about James McLevy, who lived from 1796–1875 and was a prominent Edinburgh detective in the mid-19th century. Brian Cox played McLevy in the following radio series which ran for nine series from 1999 to 2012. Ashton adapted these into novels of which Shadow of the Serpent was the first to be published in 2006. An online book club buddy recommended them to me following a discussion about detective genre and from only a few pages in I fell in love with the writing, the words and the detail. The Scotsman wrote “The key to the success of the McLevy series, however, is …. the dialogue, which somehow sounds of its time even though it slips easily across the centuries. Because he (Ashton) spends so long getting it right….” It is also speckled with vernacular, just enough to be authentic, not so much as to make it undecipherable and in need of a glossary for those not acquainted with the Scottish tongue.

For me, McLevy is a typical Scottish “hard man”, a detective who frequents the “wrong side of the tracks” in the Leith of the 1880s, the pubs, the whore houses or bawdy houses, can stand his own ground in a fight and knows the wynds, closes and backstreets of Leith intimately. But he is also a detective with a deeply ingrained and real passion for justice for all irrespective of who the victim is and of where his investigations take him and whose nose he ruffles. In this novel this takes him into the circles of political power surrounding William Gladstone's Midlothian Campaign of 1879 and 1880 in a lead up to the 1880 election defeat of Benjamin Disraeli as he tries to resolve the brutal murder of one of Leith’s prostitutes. I liked the way Ashton intertwines the political clash of Disraeli and Gladstone into this murder mystery as someone high up is out to stop Gladstone’s election – he shows the different social classes of Edinburgh at that time, the enfranchised and disenfranchised, the well heeled and the hard knuckled, each in their own way striving to better themselves and their lives. Of course we know that the historical figures cannot be the murderer, and we suspect that the woman messenger, Joanna Lightfoot, is a femme fetale, but it is the characterisation of McLevy, his side kick Mulholland, his whore house owning “friend” and supplier of “good coffee” Jean Brash that makes this book and I assume all of these will appear again in the following books in the McLevy series. I liked they way he provides McLevy’s own back story to show how his character has developed from his childhood experiences – the suicide of his mother, and being brought up by a widow woman neighbour.

ashramblings verdict 3*: an exceedingly readable murder mystery and definite worth reading another in this series

At our Creative Writing Group, the tutor brought in an article for us to use as a creative trigger along with the words “The user is about to commit an indiscretion”. The article was a round, silver hand mirror, fairly large perhaps about 6 inches across, embossed on the rear side with an animal relief .

The vanity cabinet was laden with all sorts of makeup – Maybelline, No.7, Max Factor, Revlon – she had them all. Every shade of mascara, every colour of lipstick, a huge collection of rouges and blushes and a grand variety of applicators and brushes.

Behind the cabinet was an ornately framed wall mirror, bordered by fruits of the forest, being pecked at by tiny songbirds embossed into the silver metal. But she wasn’t using that one, not yet. Its time would come. Instead she sat with her hand held one, back towards the wall.

She stretched back for her first brush and started to apply her foundation, rather white and too young one might have said for her ageing and wrinkling skin. Slowly she built up her base, then she started on her eyes, painting lines to define a shape and hiding those crows feet she so detested. Blue would be her colour today, youthfully complementing her greying irises. She chose her favourite Boots Best Buy No. 7 for this and with her smallest brush delicately applied the first layer of colour. She finished them off by fixing new lashes, long and silky, enhancing them, by using the extra spacing applicator to give the fluttering look she wanted.

She glanced into her hand mirror with satisfaction, stood up, composed herself, pulled in her tummy and turned to face her nemesis in the wall mirror asking it “Mirror, mirror on the wall…..”

by

Reminding me of reading Latin American family sagas and of first reading Khaled Hosseini, The House at the Mosque provides a sweeping account of the various branches of a household in the Iranian town of Senejan before, during and after the return of Ayatollah Khomeini .

Head of household, Aqa Jaan, is loyal, caring, thoughtful, loving, well respected but he has remained as ever, been somewhat complacent, and has let the world go by without noticing the winds of change. He struggles to realise and cope with the changes happening to the world, to Iran, to his small town, society and his family’s position, role and response to these. From the first use of television to watch the moon landings of 1969 to the modernisation and westernisation of the country under the Shah to the changed level of respect within in the community for him as elder statesman of the bazaar business community as carpet manufacture gives way to oil production and religion is politicised his eyes are finally opened to what is going on.

The writer is clearly a good storyteller: his opening chapter about the courtyard invasion of ants could stand on its own as a short story but could also be seen as symbolic of the march of change. The characters of Golbanu and Golebeh, “the grandmothers”, like two ancient giggling girls, percolates the first half of the book. They are always there, often unseen in their regime of bringing order to the household. I’d love to hear how they ended up in the house at the mosque and what they got up to on their trip to Mecca. The first half of the book build for us a picture of the life and people in and intimately associated with the house – Fakhri his wife and their children Narin, Ensi and Jawad; Aqa Jaan’s brother Nosrat always with his camera; Muezzin, the blind muezzin and potter and father of Shahbal; Zinat the old iman’s widow; Sadiq her daughter who marries Khalkal, a politicised iman , their son Lizard, and crazy Qodsi a local girl, a mystic whose incoherent ramblings provide a deceptively insightful visionary thread to the tale.

The second half ups the pace and is quite different. It is here that everything is destabilised, that change rears its ugly head and religious and political fervour run riot over all Aqa Jaan holds dear. The reader cannot help but feel for the man as he is both physically, emotional, socially and religiously caste aside as he tried to help and save the various members of his household who in one way or another fall foul of the regime. For me there were two heart rending moments in this: as he desperately tries to find a honourable burial plot for his executed son and is turned away time and time again and as his nephew, Shahbal, kills Aqa Jaan’s grandson as he assassinates an ayatollah.

The author weaves history into his story; he weaves snippets from the Koran into his story and creates a storyboard as beautiful and intricate as how he has Aqa Jaan use the colours of the feathers of migratory birds as an inspiration for his carpet designs. The translator’s note to the edition I read indicates that the passages from the Koran are a composite of several different English translations. The author also acknowledge that he has reworked the passages, taken them out of context, mixed lines from one surah with another. Whilst this may not appeal to some readers I accepted this as writer’s license and went with the flow. Likewise there could be some criticism of how he has mixed historical fact and fiction: he has taken real people, created fictionalised accounts around them and woven these into his story such as when Nosrat photographs the wife of Ayatollah Khomeini. The reader needs to be alert to separate historical fact from fiction. At the end, in the final chapter, when Aqa Jaan finally receives a letter from the exiled Shahbal he thought of like a son, this reader was left wondering how close the letter was to the writers own story – ending up in The Netherlands and working as a writer.

ashramblings verdict 4*: very readable, a very good piece of storytelling.