Writings from the group on display for 1 month in our local library

Wednesday, 28 September 2016

Tuesday, 27 September 2016

The Shadow of the Wind by Carlos Ruiz Zafón

The Shadow of the Wind (El cementerio de los libros olvidados #1)

The Shadow of the Wind (El cementerio de los libros olvidados #1)

Translated by Lucia Graves

Starting as man brings his 10 year old son Daniel to the Cemetery of Forgotten books one morning in 1945 and ending as Daniel takes his own 10 year old son Julián there in 1966, this cyclical story links the lives of two sets of people living in Barcelona across the ages via the book Daniel finds in The Cemetery of Forgotten Books. “The Shadow of the Wind” is written by Julián Carex, whose own life, his love for Penélope, his friendship with her brother Jorge runs in a parallel trejectory to those of Daniel, Beatriz and their Julián, along with loveable rogue Fermin, and Beatriz’ brother and Daniel’s friend, Tomás. The book itself is not the only link, as one man’s hatred is also following the book’s trail and as Daniel tries to uncover the story behind it and its mysterious author he inevitably clashes with him, Inspector Fumero.

There are so many parts of this multilayered book where the story hits you hard SPOILER eg the revelation of what happens to Penélope is as graphic as it is awful, how jealousy drives Fumero obsessively, feeding his same demented persona that became an assassin in the Civil War and then rose to the ranks of Police Inspector where he continues his bloodthirsty shady tactics, how grief consumes people and in Julián’s case to the point of destruction of self and work. The section which is Nuria Monfort’s letter revealing the details to Daniel is in my opinion the best written section of the book, it flows beautifully and builds up the book’s momentum when it had lulled a little.

Having recently read Zafón’s Mist Trilogy and Marina, it is easy to see how his craft has developed and how his ideas are interplaying – his interplay of light and shade of fire and shadow, as is his typically Spanish concern with their Civil War and its aftermath.

ashramblings verdict 4* Loved it, a real page turner. With the winter approaching, this is one for your fireside reading list.

I just saw that there will be a 4th book in this Cemetery of Forgotten Books Series, coming out this year in Spanish and in 2018 in English. Can’t wait.

Sunday, 25 September 2016

Liverpool Lime Street Remembered

Urgency hangs in the air,

replacing the smoke of yesteryear’s trains

with commuter chaos.

Bustling to and fro,

potential passengers;

each in their own bubble,

each with their own place to go.

I stand below the old clock tower.

Its hands counting down the minutes

that for me stand still

as the world spins by.

I wait -

a silent spectator,

a bypassed bystander -

in my quarantine dreaming.

Snared in time suspended,

as luggage is left unattended,

my lone soul stands unbefriended

until

my bubble bursts

as you appear.

© Sheila Ash 24th September 2016

Monday, 19 September 2016

The Gift

In you

A smile breaks out.In me

Eager hands are lifted up.

Anticipation anchors your eyes

upon the unknown surprise.

All of you is reprised.© Sheila Ash 19th September 2016

The candle glow that stirs within my heart

holds back the flood of tears

echoing memories of me, seen now, in you;

giving me much more than I am giving you this year.

Sunday, 18 September 2016

Post BREXIT debacle

After listening to this morning’s Andrew Marr Show #marr @MarrShow @AndrewMarr9 -

Like fridge magnet scrabble without the fridge

No backbone to corset ideas

the ramblings of the poorly constructed arguments

are like a jumble stall of unsorted miscellany.

The middle ground lies in waste post Brexit

as populist politics struggle to find a new way

to garner effective opposition

without invoking an English Nationalism of the right.

© Sheila Ash 18th September 2016

A writer’s worst nightmare

The pen nib broken.

Words, unabated,

Fly jumbled on the air

Creativity wasted

An author in despair.

© Sheila Ash 18th September 2016

Saturday, 17 September 2016

Into my box I’d put …

Into my box I’d put all the darknesses -

Into my box I’d put all the darknesses -

The dread of a young child calling for the light

The resentment gnawing the spurned lovers’ souls

The sink hole of depression

The void left by a child’s death

The shadows hiding the stalkers and trolls.

Into my box I’d put all the darknesses -

The endless cycles of starvation and drought

The chasm of economic disparity

The scourge of malaria

The catastrophe of cholera

The deprivation of spiralling poverty.

Into my box I’d put all the darknesses -

The silhouette of the unacknowledged trudging to Europe

The monstrous acts of

mad dictators, and the callousness of couch potatoes

The scab on the surface of humanity

that trade in arms to kill instead of arms to love.

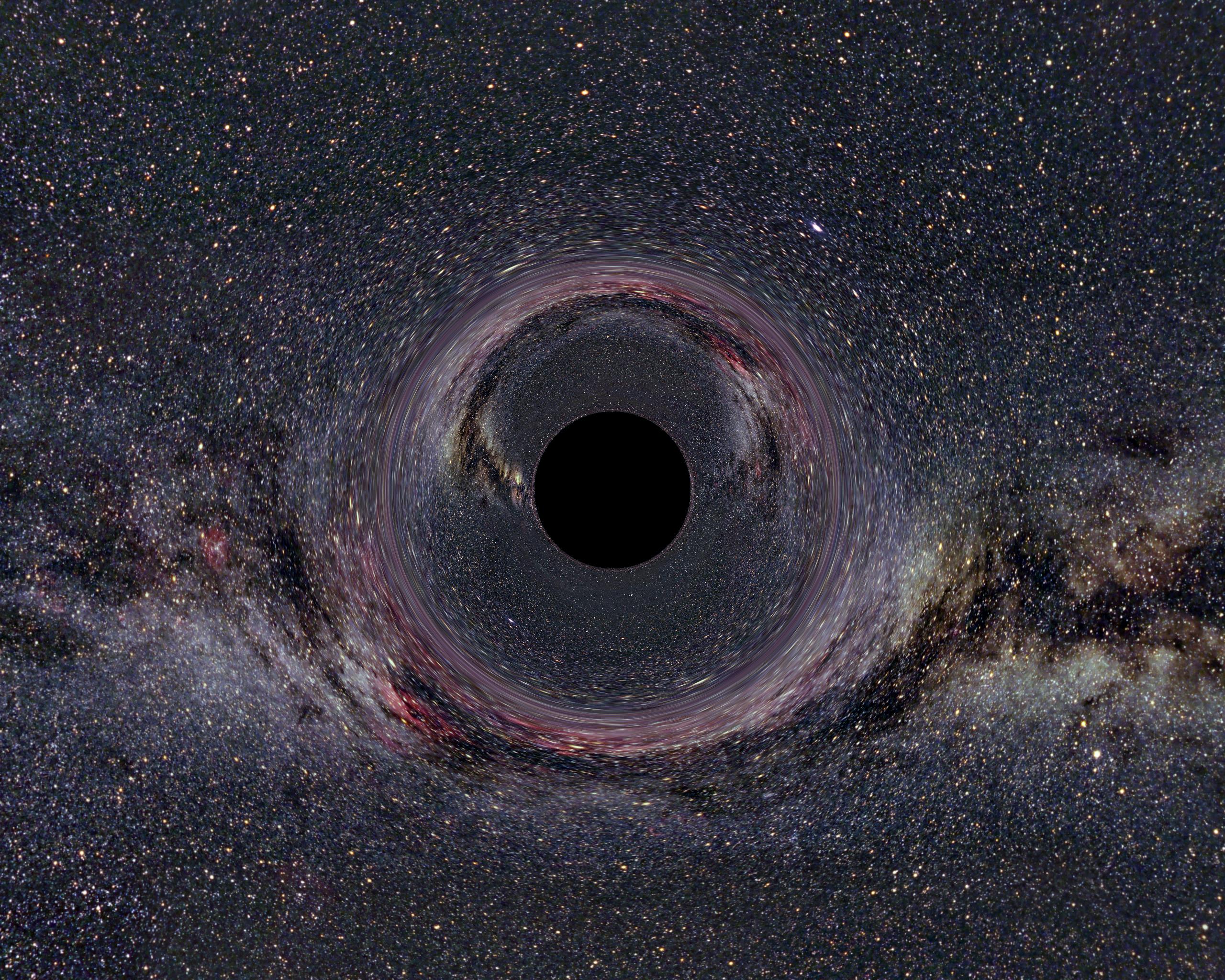

Into my box I’d put all the darknesses -

Then bind it tight in manacles and chains

and crush the only key

So guaranteeing no possibility

of ever opening up this dead man’s chest

I’d toss it far into the cosmic well of universal unacceptability.

17th September 2016

© Sheila Ash 2016

Thursday, 15 September 2016

The Meursault Investigation by Kamel Daoud

The Meursault Investigation

The Meursault Investigation

by Kamel Daoud,

Translated by John Cullen

Ever read L’Étranger (The Outsider (UK) / The Stranger (US)) by Albert Camus? Then you’ll want to read “The Meursault Investigation” by Kamel Daoud.

Camus’ book is written in two parts, before and after a murder of an unnamed Arab on the beach by its first person narrator, Meursault. He is a French Algerian, who had just attended his own mother’s funeral and who is then tried and sentenced to death for the murder. The book was written in 1942, pre the Algerian War of Independence (1954 – 1962).

In 2013 Kamel Daoud wrote The Meursault Investigation. This is a postcolonialist response to Camus’ “The Stranger “ from the perspective of the brother of the victim in Camus’ story. Daoud names the Arab, presents him as a real person, Musa, the older brother of his narrator, Harun, and explores the lives of the younger brother and his mother following the murder, the French withdrawal and Algerian Independence. Pairings with Camus’ book abound within Daoud’s book – in Camus the mother was died, in Daoud’s she is “still alive”; the woman Marie in Camus’ book and Meriem in Daoud’s; in both there is a murder etc. In effect the two books are two sides of the same coin, investigating the absurdities of life, and elucidating Algerian history and the failures of Independence.

Now the subject of a fatwa, the author Kamel Daoud continues to work as a journalist in Oran, Algeria believing that addressing the “bug” of extremism in society turns it into a greater scourge and gives it unwarranted credence. There is an interesting Interview with the author available free online. The author’s views on the West’s denial of the role of Saudi Arabia in the rise of so-called Islamic State / ISIS / Daesh are well documented and his writings provide an illuminating insight into the culture clashes now being played out in Europe and around the Med stemming from, he argues, the paradox of sex within the Arab, Moslem world, and the West’s reactive Burkini v Bikini battle. According to Daoud, writing shortly after the Cologne attacks,

“What Cologne showed is how sex is "the greatest misery in the world of Allah.

So is the refugee 'savage'? No. But he is different. And giving him papers and a place in a hostel is not enough. It is not just the physical body that needs asylum. It is also the soul that needs to be persuaded to change.

This Other (the immigrant) comes from a vast, appalling, painful universe - an Arab-Muslim world full of sexual misery, with its sick relationship towards woman, the human body, desire. Merely taking him in is not a cure."

This resulted in academic and journalistic frenzy of attacks on Daoud, accusing him of racism, self-hatred and saying “his arguments play into the hands of the anti-immigrants in Europe who can now use them to nurse their own "illusions" .”, such statements even coming from writers who had previously supported him, who had seen him as a man “who believed that people in Algeria and the wider Muslim world deserved a great deal better than military rule or Islamism, the two-entree menu they had been offered since the end of colonialism” I note with interest that article mentions a campaign in Oran which used the slogan “We are Kamel Daoud” existed way before the “Je suis Charlie” slogan in the aftermath of the Charlie Hebdo attacks. In the confusing world of Algerian politics, nevermind the maze of Arab and Moslem politics, I find myself at sea in its myriad of perspectives.

However, back to the book. Written as a conversation between Harun and an unnamed listener, a journalist, overshadowed by the ghost (of Camus/ Meursault?) in the bar, it held me throughout its exploration of the life of Haroun, his relationship with his mother – tender, resentful, angry, admiring –”Mama is still alive” “I’ll invite you to her funeral” is continually says. I’m sure if I thought more about this I could make an analysis of this book in terms of mother = Algeria and Harun’s drunken musings being the mess that Algerian society is post independence, post civil war with its high unemployment, moslemisation, and its still split personality – French / Arab / Berber. Reading it, its stream of consciousness style, I found myself recalling reading another likewise styled book many years before, namely “The Thief and the Dogs” by Naguib Mahfouz, another psychological portrait of an anguished man bent on revenge. That book open up a whole new world of reading for me. Harun too is a man who represented a certain aspect of Algerian psyche, he did not fight with the “brothers” for the revolution, he does not believe in God, and mourns the demise of liberated woman like Meriem from Algerian society, whilst remaining forever defined by the acts of both coloniser and colonised, actions beget actions, war begets war, vengeance begets vengeance, hate begets hate, a never ending spiral in which Harun in effect follows in the very footsteps of his brother’s murderer.

ashramblings verdict 5* I love what the author has done with this story, the style he used to portray it, it’s intimate relationship with its mirror image, Camus’ The Stranger, and its postcolonial currency. One of the most gripping book’s I have read this year.

Notable Reviews

By Laila Lamai in The New York Times

By Robin Yassin-Kassab in The Guardian

By Claire Messud In New York Review of Books

Wednesday, 14 September 2016

The drunken sailor’s revelry

For this week’s Creative Writing class exercise, our Tutor brought in a tallship in a bottle to use as a springboard for our writing. It was a 3-mast sailing ship in a Smirnoff bottle. I imagined an old salty dog/ sailor sitting with is drink remembering his old days on a whaling ship.

The drunken sailor’s revelry

Smirnoff on ice, clear and cold,

Yet strangely warm,

His old blood pounds and pumps up

images of glacial artic waters

Whalers riding out

Fast and furious, flapping sails bellow in the wind.

“All hands” the cry goes up.

The deck, a sudden rush of bodies pulling,

lanyards lashing, sea spray splashing,

curses lost to nature’s noises.

The hunt is on

boats bobble to the rowers’ rhythm

rocking the waves

to Shanty chanting voices.

All stilled now , as woosh,

the harpoon flies across the bow.

its target hauled home upon the flows

for chopping, slopping, slashing

until the silent, sunset sea encircles the remains of man and beast.

The ice cube’s melted in the glass.

© Sheila Ash 14th September 2016

Tuesday, 13 September 2016

The Secret History by Donna Tartt

by

It is a “why dunnit” for the first half of the book at least. I found it a bit overlong, just as I did her book The Goldfinch, while at the same time wandering what exactly could have been taken out.

This story not only revolves around a group of Classics Students, notably Greek studies, but aspects of Greek culture, aesthetics and myth are critical to the plot. Tartt clearly researches her background very well and in great depth. But at the same time I always wander whether the necessity of this context makes the story less accessible to readers, yet at the same time I seem to find that she makes it easier for the reader without this background (how many of us were taught Greek in school!) to continue with the book. Similar, to the feelings I had when reading The Goldfinch, so perhaps this is typical for reading her books :) I'll try [book:The Little Friend|775346] one day and figure it out.

I assume that Greek scholars would agree with her description of Greek rings true. She has her narrator describe Greek as "that language innocent of all quirks and cranks; a language obsessed with action, and with the joy of seeing action multiple from action, action marching relentlessly ahead and yet with more actions filing in from either side to fall into neat step at the rear, in a long straight rank of cause and effect towards what will be inevitable, the only possible end. "

This paragraph stopped me in my tracks. For those of you who know the storyline it is on pg 224 in the paperback edition, and comes just after the revelation to the narrator of Bunny's extortion of Henry, Francis et al following on from Bunny's uncovering of the incident in the woods. Being a “why dunnit”, rather than a “who dunnit*, we know what happened and here is the author making sure we are on the correct track in her unravelling of the process of getting to that conclusion of events expounded in the prologue, to that "inevitable,....only possible end" Her description of Greek, the glue which binds the characters together initially, and how at the same time this describes the train of events which subsequently binds them together - Brilliant. Of itself, this half paragraph enforces in my mind the talent that is Donna Tartt.

ashramblings review 4* No wonder she writes so few novels! Thus we can savour each one.

![Smirnoff_Red_Label_8213[1] Smirnoff_Red_Label_8213[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEj32KFeDiqBdYduqE_fN8hUK54BwHOrxD3YvTMsOPs7EPh1Vxu02pSvbc3XMAUXJYVjYsiZBgopdf7GOoPfqDw7oQB-BC4y5auE91lBBf8aCfk1K6zgBSk_3O9GUhUTLcEZpmPhXEDGPHE/?imgmax=800)

The Secret History

The Secret History